(Part One)

Blog 18, April, 2024

“If it ain’t broken … don’t fix it.”

I’m sure most readers have already heard this saying. I can recall my Dad using it more than once. It meant leave well-enough alone. Accept things as they are. Don’t meddle. You might actually break something or make things worse.

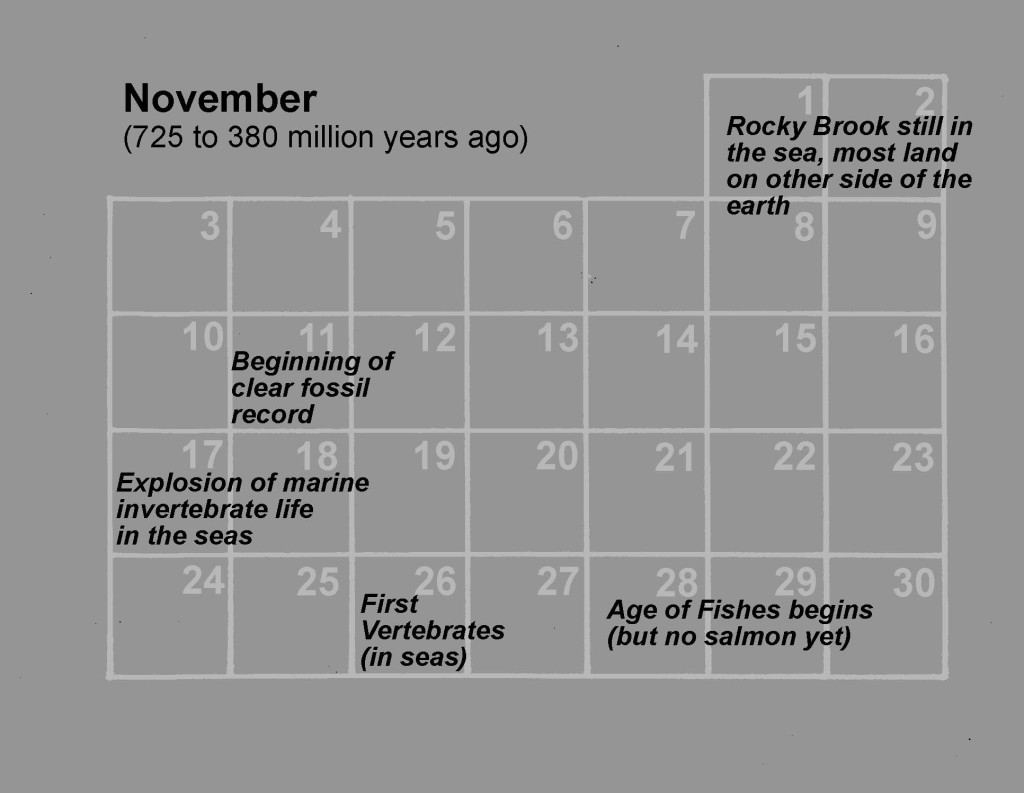

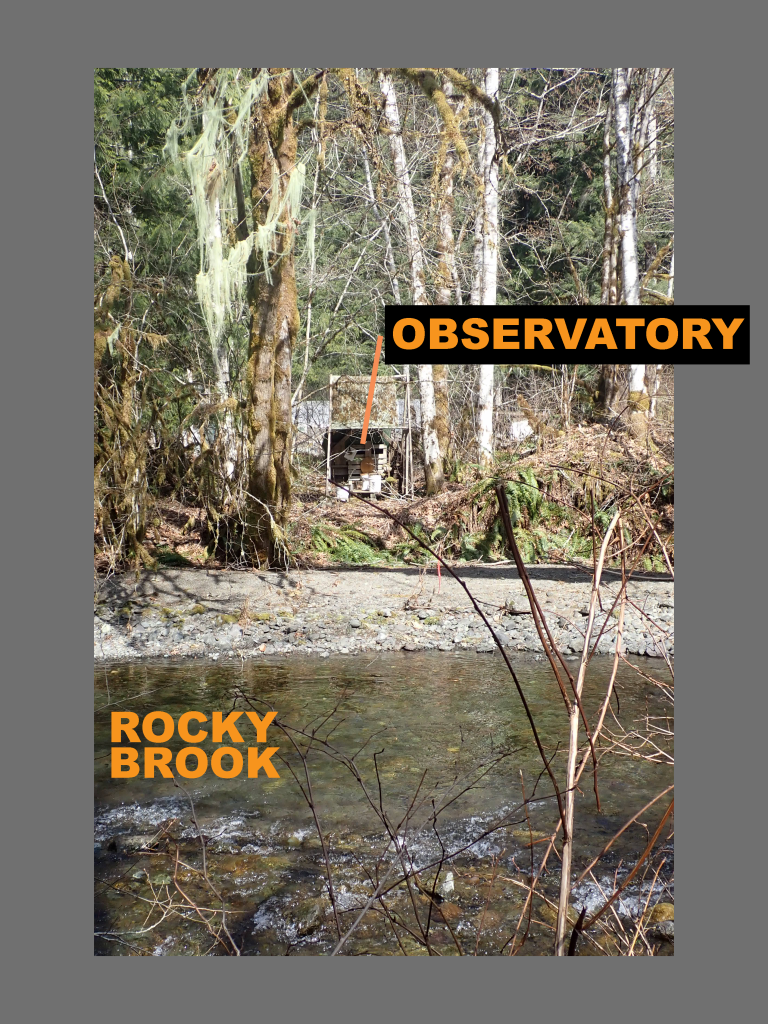

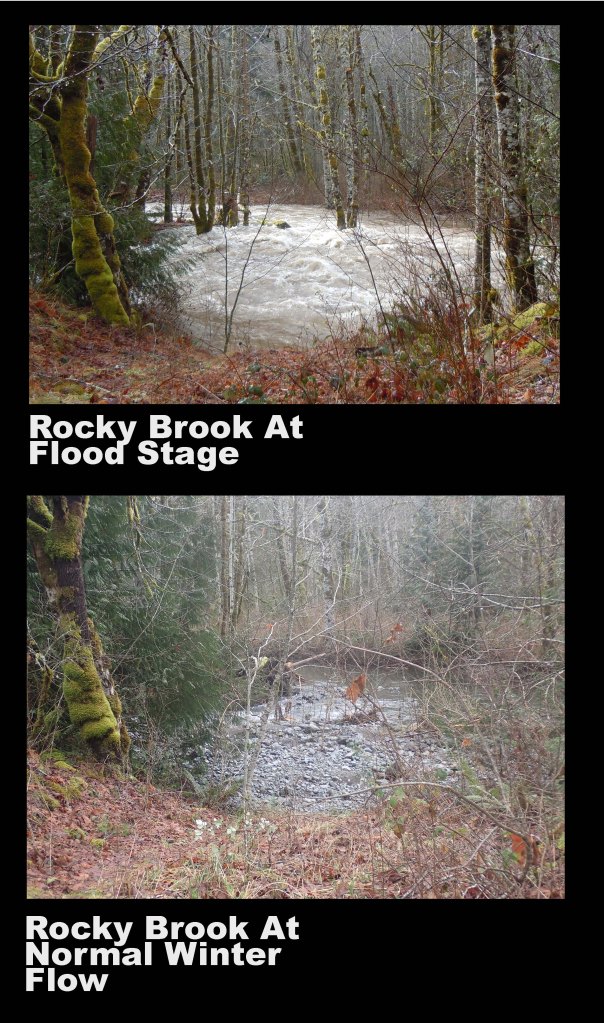

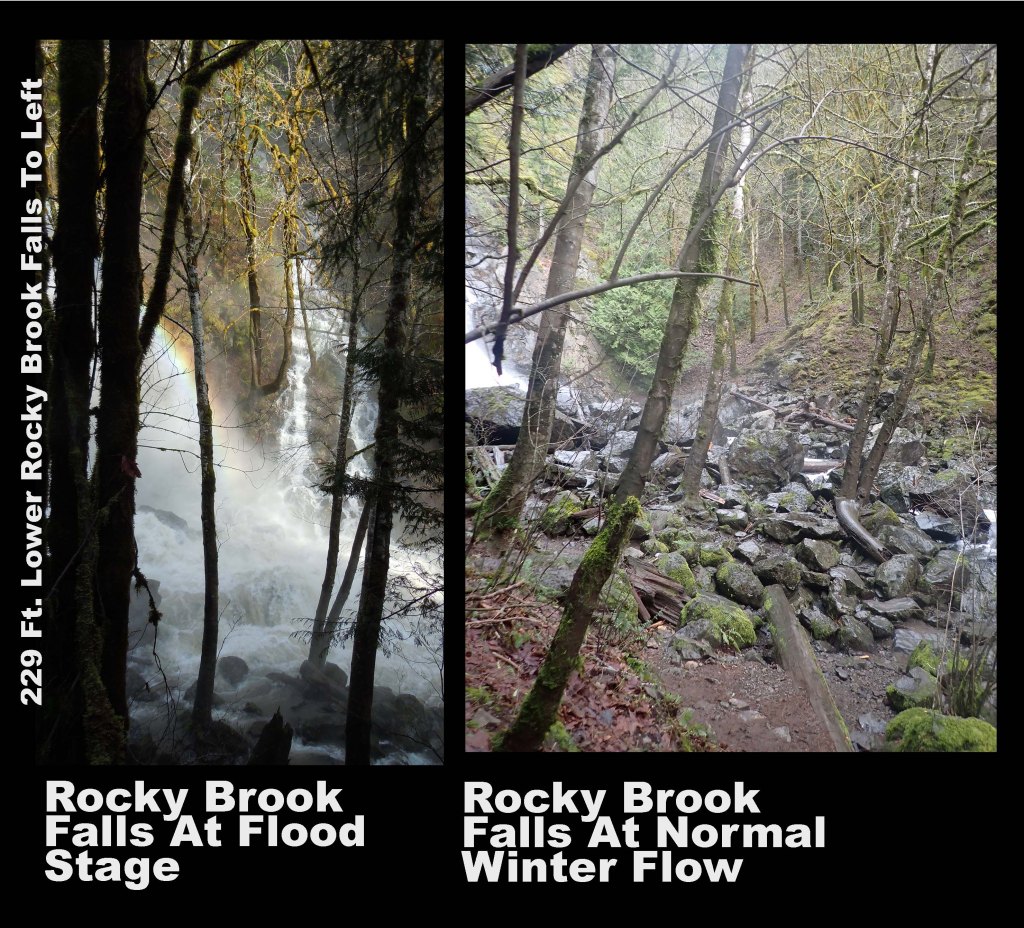

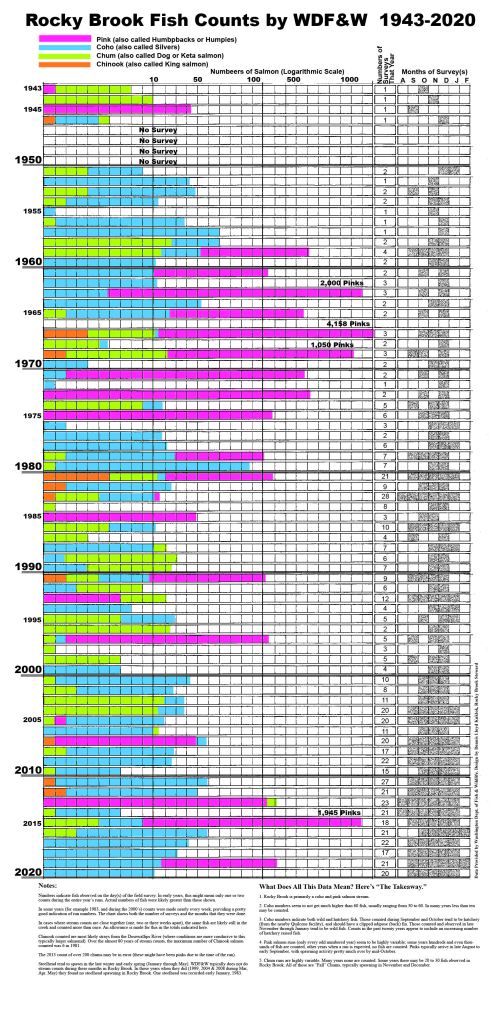

I live along two rivers; a major one, the Dosewallips, with headwaters at Anderson Glacier in Olympic National Park, and a much shorter, though year-round one, more appropriately described as a creek. It is named Rocky Brook (“Brook” seems to be the favored East-Coast word for creek; early settlers often came from out East and brought their eastern way of looking at this new world). Both support salmon runs (though Rocky Brook’s spawning habitat is less than half a mile long due to a natural barrier, 220 ft. high Rocky Brook Falls).

They no longer have the salmon and steelhead runs that they once did. Old timer’s have told me about them. Fish and Wildlife counts have supported this. So, from a salmon’s perspective, both are “broken”.

But, what to do?

Jefferson County is currently leading an effort to address, what it sees, as key parts of the problem; mostly siltation, flooding, and river channel movement within the Dosewallips’ wide floodway. The effort is currently referred to as Dosewallips River Collaborative: Community Meetings to Improve Floodplain and Habitat Resiliency, quite a mouthful and their third attempt at coming up with a name which everyone is happy with and reflects what they are doing. The focus is on a three mile stretch from Rocky Brook, where I live, up to what is called Six-Mile Bridge, as well as a downstream stretch under some high voltage power-lines. The thinking, as I understand it, is that this stretch of river is contributing to flooding and sediment build-up downstream, impacting people who live along the river all the way to where it empties into Hood Canal. When you look at the development patterns, one can’t help but notice how many structures (homes) and services (roads, power lines) have been located within or immediately adjacent to the river floodplain. Downstream from me is a subdivision where more than one of the lots has had to be abandoned due to river channel movement.

My very first Blog was called “Real Rivers Have Curves.” I wrote it after having lived here for about fifteen years. During that time I had observed the Dosewallips along my property move from one side of the floodway to the other, in some cases this amounted to 300 ft. This did not really impact me, as I both understood landscape processes enough to stay well back of what was clearly the floodplain, and could meet my needs by keeping my building, gardening and other activities away from the two river’s active floodways.

Many of my neighbors, both upstream and down, approached this situation differently. The floodplain was vacant land which could be put to good use. Most of the time it was high and dry. They built houses, located gardens, orchards and fields for cattle grazing there, often right up to the riverbank. Back in the 1940’s a few of them decided to move the main Dosewallips river channel to the far side of their property. This was a time when they had the equipment to do it, and there was little oversight on such activities. Lots of property owners did it back then, not just here but along rivers all across the country. Land was meant to be used. Rivers were supposed to stay where property owners wanted them to.

And it worked.

At least for awhile. In this case for nearly 80 years the main Dosewallips channel has remained more or less where some property owners wanted it.

But times have changed, the thinking about the river has changed (for some), and eighty years of pent-up river energy and desire to wander freely has been building up. Keeping a river under our control is possible, but it is also expensive. And, as we have learned over the past 50 or so years, it is usually not good for everyone and everything, in particular fish and forests.

This is the conundrum. Some want the river to stay the way it “always has been” (at least in their lifetimes). They see this as “normal”. They depend on this to protect their investments and interests; homes, gardens, farms, pastures, etc.. They see the world through the eyes of those who have made nature do our bidding.

Others (most scientists and a few property owners and local residents) recognize our hubris in thinking we are in charge, have not made investments in maintaining the status quo, and understand the relationship between quality fish and forest habitat and river processes. Not to mention the money saved in avoiding to pay for washed out roads and flooded homes.

Like so much in our modern world, these kinds of questions have become political and divisive. The problem is that you cannot “have your cake and eat it too”. You cannot have a healthy, natural free-flowing river and continue to allow people to use the floodway as they please.

Back to the County-led river study mentioned above. That is the challenge facing the planners, engineers and scientists leading it. In public meetings and individual encounters they quickly remind people that they will assess the situation and come up with recommendations, but implementation of any of them will depend on the support and agreement of the individual landowners. In rural Jefferson County, Washington, as in much of the country. the rights of property owners reign supreme and rural people often distrust “city people” (where the planners seem to be located). Even in this remote valley where I live, conspiracy theories abound about “the government” having “secret plans and hidden agendas” to take over one’s property for one reason or another.

As a rural property owner forty miles from the County seat of government, I can understand this. I often resent the fact that to build my cabin I have to adhere to a building code which is city/suburb and industrial construction material (a.k.a. buy it from some store) oriented, and makes it hard for me to use my own timber as well as employ non-mainstream building techniques (including using straw bales as insulation, a cob (earthen) wall, and a “poured adobe floor”.

At the same time, I have a pretty good understanding of the needs of salmon, the processes of rivers, and the health of forest ecosystems. I agree that the river is broken in that its function as salmon habitat is far below its potential and historic levels, and actions need to be taken for the sake of salmon, forests and the rivers. Doing something is in my immediate and long-term interest.

And I understand that by not doing something, by ignoring the problem, we all will at some point pay, either by radical changes within our property (loss of land and structures to a changing river or major flood event) or by expensive repairs to the public infrastructure (roads, power lines, emergency services) we depend on.

The planners are in a process of evaluating the problems, identifying possible actions to deal with it, gain property owner and community support, secure available funds, and (after seemingly endless meetings and years of study) actually do something. These things take time and money, lots of both.

So, what are some of the “tools” in a river repair kit? Here are five of the most commonly employed actions.

- Plantings

Almost all river restoration projects include some type of replanting, usually trees. When the Elwha dams to the northwest of me were removed, the project called for an elaborate and costly program for replanting the newly exposed riverbanks and terraces, including a plant nursery to raise native plants. What I found interesting about this effort was seeing how quickly the river ecosystem itself acted to revegetate these areas with robust stands of alders, willows and poplars, as well as a variety of shrubs, wildflowers and grasses. One couldn’t help but wonder if the expensive replanting program was necessary, at least at the scale and cost it was implemented. Since these were the largest dams to be removed up to that time, it was a learning experience, and hopefully lessons here will be employed in the other removals underway, specifically those on the Klamath river in southern Oregon and northern California.

I also have observed that where there are road failures along the Dosewallips road, they typically replant the rock and bolder embankments with trees, most often Douglas Fir. Rarely do these threes survive. A reforestation expert told me that it take at least two years for young conifer seedlings to get a root system capable of reaching ground water in order for it to survive our long summer dry periods. The road embankments where they are planted have little to no soil and virtually no water retention capacity. It’s almost like the engineers feel they have to do something, check off the box requiring “replanting” in order to get the State and Federal matching funs, and they quickly forget about it. I doubt if they even go back to look at the situation two years later and see no young trees and wonder why. Of course, trees will eventually arrive, but in these difficult sites, it can take decades.

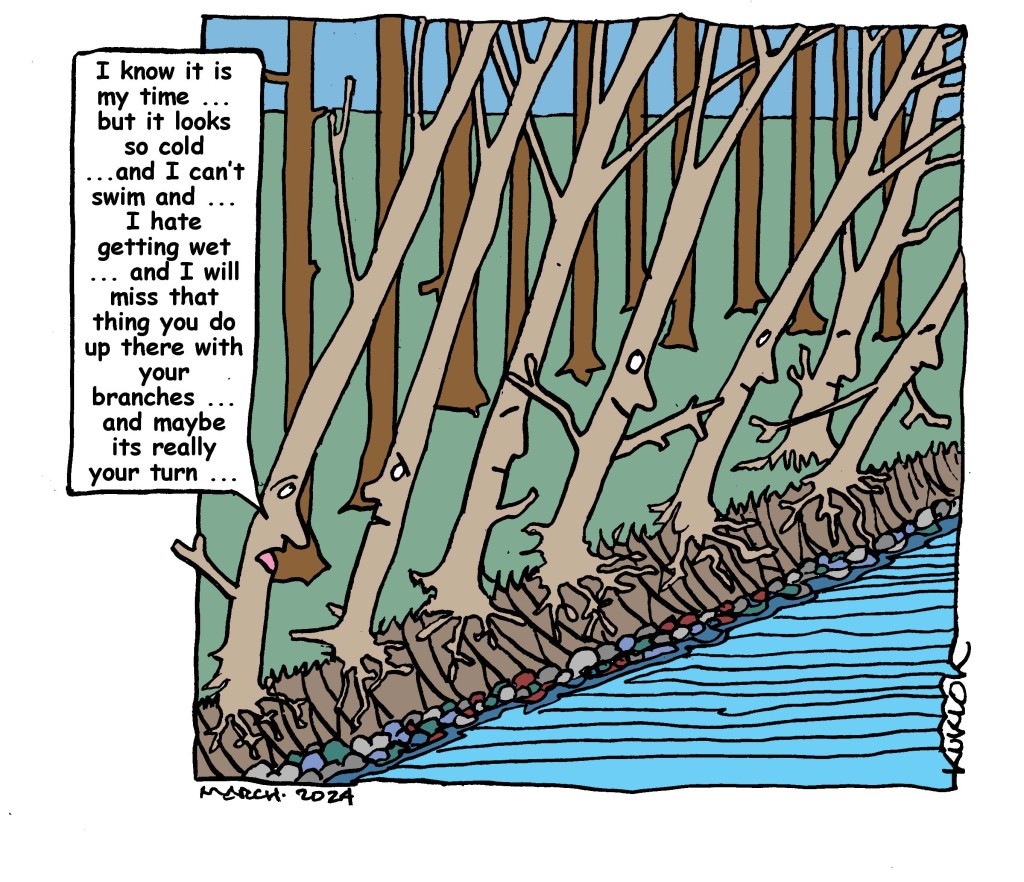

On my property, the intervention that I most want from this current county-led restoration project is tree planting in conjunction with elk fencing. My long term river restoration strategy on my twenty some acres of floodplain includes saving the big cottonwoods and cedars that I already have, and establishing new stands near them, slowly returning the river to a forest of large trees like it was before we settled the area.

Heavy elk grazing leaves much of my riverfront property devoid of emergent trees, with mostly alders surviving as can be seen here. The alders eventually die, resulting in more open, meadow-like conditions rather than a riverside forest dominated by willows, cottonwoods, cedars and firs.

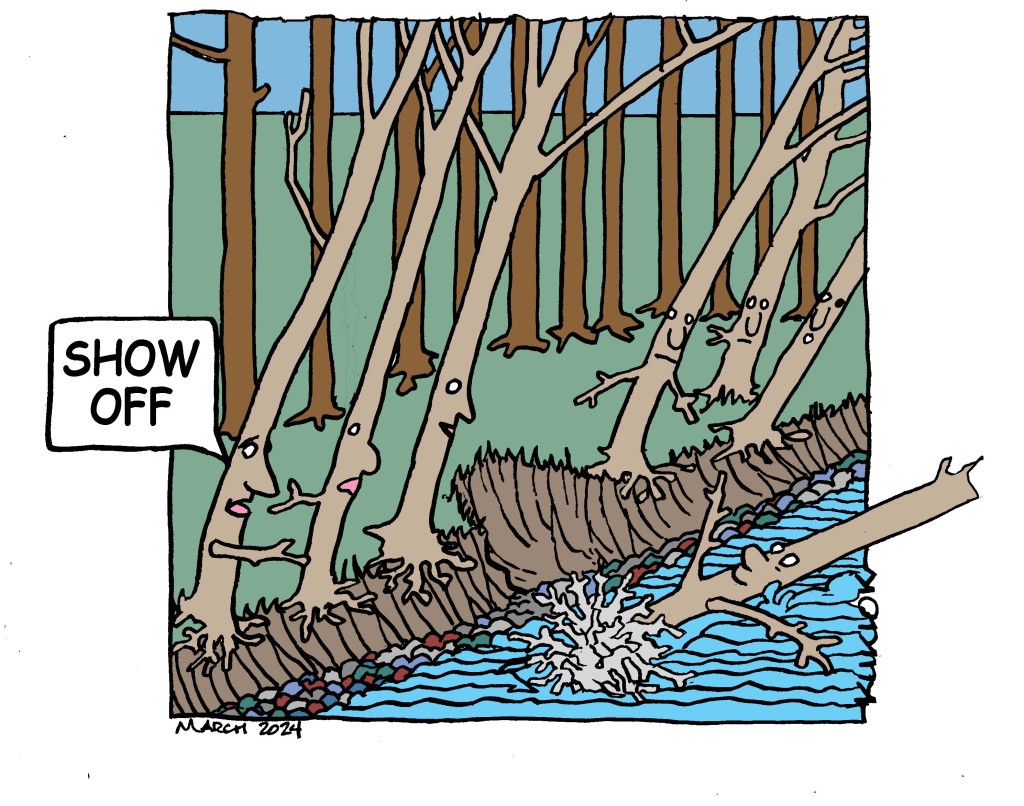

2. Large Wood (LW) or Large Woody Debris (LWD)

Historically, all salmon supporting rivers and streams in the Pacific Northwest were chock full of dead trees (often including huge root wads). Parts of them would get buried under gravel, sand and silt and could remain for decades and even centuries. In river restoration parlance, this kind of material is referred to as large wood or large woody debris. It is not uncommon for projects to bring in truckloads of big root-wads and trunks from afar and position them in places where they help to protect riverbanks, direct channel flow, create fish-friendly pools, and capture other wood being washed down from upstream. In many situations they can even create log dams across an entire channel where water is able to move through, but at a slower rate.

In a natural, wild river system, such accumulations of woody materials will be constantly changing position in response to river flooding and channel changes. Here in much of the Pacific Northwest, this is no longer the case, as logging tends to remove the big trees entirely and replace them with smaller ones. From a river’s perspective, trees need to be big to be able to influence the flow and create all the pools and micro-habitats that fish and other wildlife desire.

Insert photo 3

The Dosewallips floodplain along my property does “capture” some large trees, including root-wads such as this, however they are becoming fewer and less frequent as such trees become scarcer. The one shown here could continue to travel downstream in the next high water event, or could snag up and become buried, where it could influence water flow patterns for decades.

3. Engineered Log Jams (ELJs)/Diversion Structures

A wild, free flowing river that includes lots of large, older trees will naturally have log piles and log jams. Trees, even large ones, can float in floods, moving surprisingly large distances. Invariably they will snag up or be beached someplace, where they can entangle other trees, eventually creating considerable structures. They can last decades.

River engineers try to recreate such barriers. Usually the intent is to divert or redirect flow, sometimes away from roads and structures, sometimes towards former or new channels, sometimes both. While diversion structures can be as formidable as concrete or steel, here in the Pacific Northwest engineers seem to prefer working primarily with logs and cables, they tend to look more natural and cost less).

Here on the Dosewallips, there have been two major projects incorporating ELJs. One is upstream from me (I am at about mile 3, this intervention is at about mile 7). It is about ten years old, and at this stage is hard for most people to even recognize, as trees, shrubs and groundcovers have grown up. I am hoping to be able to talk to the engineers who designed it and get a sense as to how well it met the intended objectives and what can be learned from it.

The other project is at he Dosewallips River estuary within Dosewallips State Park. Historically, the park did what most people did, it located structures (restrooms) and uses (drive-in campsites) right next to the river floodplain. Seemed natural. That is where people wanted to be, the river was a big part of the attractiveness of the Park. However, times have changed. State Parks seem to be thinking far into the future, preparing for both sea level rising here as well as recognizing the importance of letting the river follow its natural instincts.

Thus, they have abandoned a major part of the camping area and implemented a project that strives to return that part of the river to some of its former channels. They have employed a few ELJ diversion structures and some channel dredging, setting the stage for the river to do much of the work. One can already observe some new channels which have pools, riffles and gravel beds seemingly perfect for spawning salmon, especially chums and pinks which tend to like the lower portions of rivers, close to salt water.

I hope to watch this area and comment on how well it is working in future blogs. The only real challenge with this work that I see is the failure to recognize the role of elk in limiting natural revegetation (replanting does not appear to be part of the work to date). The herd of seventy-plus animals uses this area extensively, and is a primary attraction for visitors and locals. I would suggest fencing off at least a part of the restoration area and comparing it with areas where elk grazing is allowed to see if key large trees such as poplar and western red cedar (both preferred browse species by elk) return naturally.

4. Culverts and Bridges

Throughout the Pacific Northwest, returning salmon have long been prevented from returning to many parts of a river due to undersized and improperly installed culverts and bridges. This is especially the case in areas where considerable logging has taken place. There, the objective is to allow trucks and equipment to cross creeks and streams in as inexpensive a manner as possible, without much thought to how these structures will affect fish movement. Over time, erosion on one end of a culvert can result in an elevation change which is too high for salmon to jump.

Many river restoration projects have focused on removing culverts where they are no longer needed, putting in bigger, better designed ones (or bridges) where they still are, and replacing bridges which in some way make salmon movement up and downstream either difficult or impossible.

Upstream from me (between mile 7 and 8 of the Dosewallips), in the twenty-some years since I have lived here, I have observed culvert replacement to accommodate the Forest Service road accessing trailheads, campgrounds, and Olympic National Park. Three culverts have been installed, each one larger than the previous one. As it stands, even the latest (which appears to be 8 ft diameter) has failed during heavy winter stream flows. It looks like they have just given up: now cars just park on this side of the failed culverts and people have to walk or bike from there. This adds almost seven miles of walking to get into the National Park, and was the only way that elderly or people with disabilities could drive into the Park on the entire east (Hood Canal) side.

5. Earthworks (Dikes, Embankments, Channelization)

Historically, river management and restoration projects have emphasized small and large earthworks. These can be readily engineered, use available heavy equipment, materials and skills, and give seemingly immediate results. The large scale of such projects often meets funding partnerships with Federal and State agencies.

Unfortunately, from a salmon or reforestation perspective, historically such projects have been more harmful than helpful. But this is changing. Both of the local salmon enhancement groups near me have embraced larger scale river modifications; in each case removing dikes and man-made channels. Hood Canal Salmon Enhancement Group (HCSEG) has done this in the lower Little Quilcene estuary just to the north of me. And the North Olympic Salmon Coalition (NOSC) has done it along the Snow Creek estuary, two watersheds to the north.

Closer to home, I am just now learning about a dike on the lower Dosewallips. It was built years ago to keep the river from wandering into the developing parts of the Brinnon community. Apparently is has not been maintained and to a certain extent has been largely forgotten. Yet, if it fails, significant property in what is considered the “center” of Brinnon could be impacted, including the Post Office, Fire Station, School, and many residences.

And this old dike is being challenged from two fronts. First, river flooding and channel movement continues to weaken it. Second, since much of this possibly impacted area is less than five feet above sea-level, its rise could bring in water from the other direction, Hood Canal. The County river study, mentioned above, will apparently be expanded to look at this key issue, one that will determine the future of the town as we know it. We will be faced with a question many seaside communities are having to answer; invest in protecting what we have even though it is situated in areas subject to future flooding, or start to move things uphill. The State Park seems to be moving in the latter direction, as they recently abandoned the most vulnerable campsites. Either way it will not be cheap.

These are the most commonly employed “tools” in river restoration work. There is another one, dam removal which is the most expensive and challenging one. At the same time it could have the most significant impact on salmon populations that historically accessed spawning and rearing areas within the damed river systems. It is encouraging to see that this option is being seen as more of a possibility, and those of us who value wild salmon here in the Pacific Northwest continue to hope for and work towards the removal of the four lower Snake River dams along the Columbia system.

The Snake River dam removal option continues to evolve, from “absolutely not” twenty years ago to “a possibility” today. My understanding is that in September, 2020, a “final record of decision” was issued on the Federal Columbia River Power System’s Environmental impact Statement. The controversial decision was that dam breaching was not a viable option. This decision was challenged in court by the States of Oregon and Washington as well as the Nez Perce Tribe, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation. After nearly three years of negotiations, on December 14, 2023, the Federal Government announced an agreement with the above mentioned plaintiffs that was favorable to dam breaching. Quite likely there will continue to be new litigation on this decision, with no real end in site. For the latest on this subject, go to columbiariverkeepers.org or americanrivers.org. Alternative points of view can be found at nwriverpartners.org or Public Power Council (ppcpdx.org.

Restoration Tools are not all that I think about in what it takes to fix a river. I am saving that for the next blog (number 19) … look for it on June 1 or thereabouts.

Dennis Lloyd Kuklok

Rocky Brook, March 25, 2024

Leave a comment